Symphony No. 98 in B-flat major, Hob. I:98: IV. Finale. Presto

Joseph Haydn (31 March or 1 April 1732–31 May 1809) was a leading composer … Read Full Bio ↴Joseph Haydn (31 March or 1 April 1732–31 May 1809) was a leading composer of the Classical period, called the "Father of the Symphony" and "Father of the String Quartet".

The name "Franz" was not used in the composer's lifetime; scholars, along with an increasing number of music publishers and recording companies, now use the historically more accurate form of his name, rendered in English as "Joseph Haydn".

A life-long resident of Austria, Haydn spent most of his career as a court musician for the wealthy Eszterházy family on their remote estate. Being isolated from other composers and trends in music until the later part of his long life, he was, as he put it, "forced to become original".

Joseph Haydn was the brother of Michael Haydn, himself a highly regarded composer at the court of Archbishop-Prince Hieronymous von Colloredo who also had in his employ Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and father Leopold Mozart. Haydn had a third brother, Johann Evangelist Haydn, a tenor singer.

Joseph Haydn was born in 1732 in Rohrau, Austria village near the Hungarian border. His father was Matthias Haydn, a wheelwright who also served as "Marktrichter", an office akin to village mayor. Haydn's mother, the former Maria Koller, had previously worked as a cook in the palace of Count Harrach, the presiding aristocrat of Rohrau. Neither parent could read music. However, Matthias was an enthusiastic folk musician, who during the journeyman period of his career had taught himself to play the harp. According to Haydn's later reminiscences, his childhood family was extremely musical, and frequently sang together and with their neighbors.

Haydn's parents were perceptive enough to notice that their son was musically talented and knew that in Rohrau he would have no chance to obtain any serious musical training. It was for this reason that they accepted a proposal from their relative Johann Matthias Franck, the schoolmaster and choirmaster in Hainburg, that Haydn be apprenticed to Franck in his home to train as a musician. Haydn thus went off with Franck to Hainburg (ten miles away) and never again lived with his parents. At the time he was not quite six.

Life in the Franck household was not easy for Haydn, who later remembered being frequently hungry as well as constantly humiliated by the filthy state of his clothing. However, he did begin his musical training there, and soon was able to play both harpsichord and violin. The people of Hainburg were soon hearing him sing soprano parts in the church choir.

There is reason to think that Haydn's singing impressed those who heard him, because two years later (1740), he was brought to the attention of Georg von Reutter, the director of music in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, who was touring the provinces looking for talented choirboys. Haydn passed his audition with Reutter, and soon moved off to Vienna, where he worked for the next nine years as a chorister, the last four in the company of his younger brother Michael.

Like Franck before him, Reutter didn't always bother to make sure Haydn was properly fed. The young Haydn greatly looked forward to performances before aristocratic audiences, where the singers sometimes had the opportunity to satisfy their hunger by devouring the refreshments. Reutter also did little to further his choristers' musical education. However, St. Stephen's was at the time one of the leading, musical centers in Europe, where new music by leading composers was constantly being performed. Haydn was able to learn a great deal by osmosis simply by serving as a professional musician there.

In 1749, Haydn had matured physically to the point that he was no longer able to sing high choral parts. On a weak pretext, he was summarily dismissed from his job. He evidently spent one night homeless on a park bench, but was taken in by friends and began to pursue a career as a freelance musician. During this arduous period, which lasted ten years, Haydn worked many different jobs, including valet–accompanist for the Italian composer Nicola Porpora, from whom he later said he learned "the true fundamentals of composition". He laboured to fill the gaps in his training, and eventually wrote his first string quartets and his first opera. During this time Haydn's professional reputation gradually increased.

In 1759, or 1757 according to the New Grove Encyclopedia, Haydn received his first important position, that of Kapellmeister (music director) for Count Karl von Morzin. In this capacity, he directed the count's small orchestra, and for this ensemble wrote his first symphonies. Count Morzin soon suffered financial reverses that forced him to dismiss his musical establishment, but Haydn was quickly offered a similar job (1761) as assistant Kapellmeister to the Eszterházy family, one of the wealthiest and most important in the Austrian Empire. When the old Kapellmeister, Gregor Werner, died in 1766, Haydn was elevated to full Kapellmeister.

As a liveried servant of the Eszterházys, Haydn followed them as they moved among their three main residences: the family seat in Eisenstadt, their winter palace in Vienna, and Eszterháza, a grand new palace built in rural Hungary in the 1760s. Haydn had a huge range of responsibilities, including composition, running the orchestra, playing chamber music for and with his patrons, and eventually the mounting of operatic productions. Despite the backbreaking workload, Haydn considered himself fortunate to have his job. The Eszterházy princes (first Paul Anton, then most importantly Nikolaus I) were musical connoisseurs who appreciated his work and gave him the conditions needed for his artistic development, including daily access to his own small orchestra.

In 1760, with the security of a Kapellmeister position, Haydn married. He and his wife, the former Maria Anna Keller, did not get along, and they produced no children. Haydn may have had one or more children with Luigia Polzelli, a singer in the Eszterházy establishment with whom he carried on a long-term love affair, and often wrote to on his travels.

During the nearly thirty years that Haydn worked in the Eszterházy household, he produced a flood of compositions, and his musical style became ever more developed. His popularity in the outside world also increased. Gradually, Haydn came to write as much for publication as for his employer, and several important works of this period, such as the Paris symphonies (1785–6) and the original orchestral version of The Seven Last Words of Christ (1786), were commissions from abroad.

Around 1781 Haydn established a friendship with Mozart, whose work he had already been influencing by example for many years. According to later testimony by Stephen Storace, the two composers occasionally played in string quartets together. Haydn was hugely impressed with Mozart's work, and in various ways tried to help the younger composer. During the years 1782 to 1785, Mozart wrote a set of string quartets thought to be inspired by Haydn's Opus 33 series. On completion he dedicated them to Haydn, a very unusual thing to do at a time when dedicatees were usually aristocrats. The extremely close 'brotherly' Mozart-Haydn connection may be an expression of Freemasonic sympathies as well: Mozart and Haydn were members of the same Masonic lodge. Mozart joined in 1784 in the middle of writing those string quartets subsequently dedicated to his Masonic brother Haydn. This lodge was a specifically Catholic rather than a deistic one.

In 1789, Haydn developed another friendship with Maria Anna von Genzinger (1750–93), the wife of Prince Nicolaus's personal physician in Vienna. Their relationship, documented in Haydn's letters, was evidently intense but platonic. The letters express Haydn's sense of loneliness and melancholy at his long isolation at Eszterháza. Genzinger's premature death in 1793 was a blow to Haydn, and his F minor variations for piano, Hob. XVII:6, which are unusual in Haydn's work for their tone of impassioned tragedy, may have been written as response to her death.

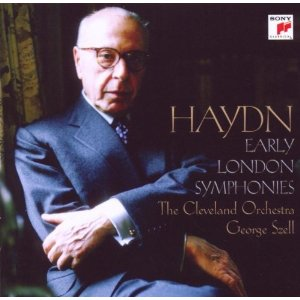

The London journeys

In 1790, Prince Nikolaus died and was succeeded by a thoroughly unmusical prince who dismissed the entire musical establishment and put Haydn on a pension. Thus freed of his obligations, Haydn was able to accept a lucrative offer from Johann Peter Salomon, a German impresario, to visit England and conduct new symphonies with a large orchestra.

The visit (1791-2), along with a repeat visit (1794-5), was a huge success. Audiences flocked to Haydn's concerts, and he quickly achieved wealth and fame: one review called him "incomparable." Musically, the visits to England generated some of Haydn's best-known work, including the Surprise, Military, Drumroll, and London symphonies, the Rider quartet, and the Gypsy Rondo piano trio.

The only misstep in the venture was an opera, L'anima del filosofo, which Haydn was contracted to compose, and paid a substantial sum of money for. Only one aria was sung at the time, and 11 numbers were published; the entire opera was not performed until 1950.

Final years in Vienna

Haydn actually considered becoming an English citizen and settling permanently, as composers such as Handel had before him, but decided on a different course. He returned to Vienna, had a large house built for himself, and turned to the composition of large religious works for chorus and orchestra. These include his two great oratorios The Creation and The Seasons and six masses for the Eszterházy family, which by this time was once again headed by a musically-inclined prince. Haydn also composed the last nine in his long series of string quartets, including the Emperor, Sunrise, and Fifths quartets. Despite his increasing age, Haydn looked to the future, exclaiming once in a letter, "how much remains to be done in this glorious art!"

In 1802, Haydn found that an illness from which he had been suffering for some time had increased greatly in severity to the point that he became physically unable to compose. This was doubtless very difficult for him because, as he acknowledged, the flow of fresh musical ideas waiting to be worked out as compositions did not cease. Haydn was well cared for by his servants, and he received many visitors and public honours during his last years, but they cannot have been very happy years for him. During his illness, Haydn often found solace by sitting at the piano and playing Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser, which he had composed himself as a patriotic gesture in 1797. This melody later became used for the Austrian and German national anthems, and is the national anthem of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Haydn died in 1809 following an attack on Vienna by the French army under Napoleon. Among his last words was his attempt to calm and reassure his servants as cannon shots fell on the neighbourhood.

Character and appearance

Haydn was known among his contemporaries for his kindly, optimistic, and congenial personality. He had a robust sense of humour, evident in his love of practical jokes and often apparent in his music. He was particularly respected by the Eszterházy court musicians whom he supervised, as he maintained a cordial working atmosphere and effectively represented the musicians' interests with their employer; see Papa Haydn.

Haydn was a devout Catholic who often turned to his rosary when he had trouble composing, a practice that he usually found to be effective. When he finished a composition, he would write "Laus deo" ("praise be to God") or some similar expression at the end of the manuscript. His favourite hobbies were hunting and fishing.

Haydn was short in stature, perhaps as a result of having been underfed throughout most of his youth. Like many in his day, he was a survivor of smallpox and his face was pitted with the scars of this disease. Haydn was quite surprised when women flocked to him during his London visits as he did not consider himself to be handsome.

About a dozen portraits of Haydn exist, although they disagree sufficiently that, other than what is noted above, we would have little idea what Haydn looked like were it not also for the existence of a lifelike wax bust and Haydn's death mask. Both are in the Haydnhaus in Vienna, a museum dedicated to the composer. All but one of the portraits show Haydn wearing the grey powdered wig fashionable for men in the 18th century, and from the one exception we learn that Haydn was bald in adulthood.

Works

Haydn is often described as the "father" of the classical symphony and string quartet. In fact, the symphony was already a well-established form before Haydn began his compositional career, with distinguished examples by Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach among others, but Haydn's symphonies are the earliest to remain in "standard" repertoire. His parenthood of the string quartet, however, is beyond doubt: he essentially invented this medium singlehandedly. He also wrote many piano sonatas, piano trios, divertimentos and masses, which became the foundation for the Classical style in these compositional types. He also wrote other types of chamber music, as well as operas and concerti, although such compositions are now less known. Although other composers were prominent in the earlier Classical period, notably C.P.E. Bach in the field of the keyboard sonata (the harpsichord and clavichord were equally popular with the piano in this era) and J.C. Bach and Leopold Mozart in the symphony, Haydn was undoubtedly the strongest overall influence on musical style in this era.

The development of sonata form into a subtle and flexible mode of musical expression, which became the dominant force in Classical musical thought, owed most to Haydn and those who followed his ideas. His sense of formal inventiveness also led him to integrate the fugue into the classical style and to enrich the rondo form with more cohesive tonal logic, (see sonata rondo form). Haydn was also the principal exponent of the double variation form, that is variations on two alternating themes, which are often major and minor mode versions of each other.

The name "Franz" was not used in the composer's lifetime; scholars, along with an increasing number of music publishers and recording companies, now use the historically more accurate form of his name, rendered in English as "Joseph Haydn".

A life-long resident of Austria, Haydn spent most of his career as a court musician for the wealthy Eszterházy family on their remote estate. Being isolated from other composers and trends in music until the later part of his long life, he was, as he put it, "forced to become original".

Joseph Haydn was the brother of Michael Haydn, himself a highly regarded composer at the court of Archbishop-Prince Hieronymous von Colloredo who also had in his employ Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and father Leopold Mozart. Haydn had a third brother, Johann Evangelist Haydn, a tenor singer.

Joseph Haydn was born in 1732 in Rohrau, Austria village near the Hungarian border. His father was Matthias Haydn, a wheelwright who also served as "Marktrichter", an office akin to village mayor. Haydn's mother, the former Maria Koller, had previously worked as a cook in the palace of Count Harrach, the presiding aristocrat of Rohrau. Neither parent could read music. However, Matthias was an enthusiastic folk musician, who during the journeyman period of his career had taught himself to play the harp. According to Haydn's later reminiscences, his childhood family was extremely musical, and frequently sang together and with their neighbors.

Haydn's parents were perceptive enough to notice that their son was musically talented and knew that in Rohrau he would have no chance to obtain any serious musical training. It was for this reason that they accepted a proposal from their relative Johann Matthias Franck, the schoolmaster and choirmaster in Hainburg, that Haydn be apprenticed to Franck in his home to train as a musician. Haydn thus went off with Franck to Hainburg (ten miles away) and never again lived with his parents. At the time he was not quite six.

Life in the Franck household was not easy for Haydn, who later remembered being frequently hungry as well as constantly humiliated by the filthy state of his clothing. However, he did begin his musical training there, and soon was able to play both harpsichord and violin. The people of Hainburg were soon hearing him sing soprano parts in the church choir.

There is reason to think that Haydn's singing impressed those who heard him, because two years later (1740), he was brought to the attention of Georg von Reutter, the director of music in St. Stephen's Cathedral in Vienna, who was touring the provinces looking for talented choirboys. Haydn passed his audition with Reutter, and soon moved off to Vienna, where he worked for the next nine years as a chorister, the last four in the company of his younger brother Michael.

Like Franck before him, Reutter didn't always bother to make sure Haydn was properly fed. The young Haydn greatly looked forward to performances before aristocratic audiences, where the singers sometimes had the opportunity to satisfy their hunger by devouring the refreshments. Reutter also did little to further his choristers' musical education. However, St. Stephen's was at the time one of the leading, musical centers in Europe, where new music by leading composers was constantly being performed. Haydn was able to learn a great deal by osmosis simply by serving as a professional musician there.

In 1749, Haydn had matured physically to the point that he was no longer able to sing high choral parts. On a weak pretext, he was summarily dismissed from his job. He evidently spent one night homeless on a park bench, but was taken in by friends and began to pursue a career as a freelance musician. During this arduous period, which lasted ten years, Haydn worked many different jobs, including valet–accompanist for the Italian composer Nicola Porpora, from whom he later said he learned "the true fundamentals of composition". He laboured to fill the gaps in his training, and eventually wrote his first string quartets and his first opera. During this time Haydn's professional reputation gradually increased.

In 1759, or 1757 according to the New Grove Encyclopedia, Haydn received his first important position, that of Kapellmeister (music director) for Count Karl von Morzin. In this capacity, he directed the count's small orchestra, and for this ensemble wrote his first symphonies. Count Morzin soon suffered financial reverses that forced him to dismiss his musical establishment, but Haydn was quickly offered a similar job (1761) as assistant Kapellmeister to the Eszterházy family, one of the wealthiest and most important in the Austrian Empire. When the old Kapellmeister, Gregor Werner, died in 1766, Haydn was elevated to full Kapellmeister.

As a liveried servant of the Eszterházys, Haydn followed them as they moved among their three main residences: the family seat in Eisenstadt, their winter palace in Vienna, and Eszterháza, a grand new palace built in rural Hungary in the 1760s. Haydn had a huge range of responsibilities, including composition, running the orchestra, playing chamber music for and with his patrons, and eventually the mounting of operatic productions. Despite the backbreaking workload, Haydn considered himself fortunate to have his job. The Eszterházy princes (first Paul Anton, then most importantly Nikolaus I) were musical connoisseurs who appreciated his work and gave him the conditions needed for his artistic development, including daily access to his own small orchestra.

In 1760, with the security of a Kapellmeister position, Haydn married. He and his wife, the former Maria Anna Keller, did not get along, and they produced no children. Haydn may have had one or more children with Luigia Polzelli, a singer in the Eszterházy establishment with whom he carried on a long-term love affair, and often wrote to on his travels.

During the nearly thirty years that Haydn worked in the Eszterházy household, he produced a flood of compositions, and his musical style became ever more developed. His popularity in the outside world also increased. Gradually, Haydn came to write as much for publication as for his employer, and several important works of this period, such as the Paris symphonies (1785–6) and the original orchestral version of The Seven Last Words of Christ (1786), were commissions from abroad.

Around 1781 Haydn established a friendship with Mozart, whose work he had already been influencing by example for many years. According to later testimony by Stephen Storace, the two composers occasionally played in string quartets together. Haydn was hugely impressed with Mozart's work, and in various ways tried to help the younger composer. During the years 1782 to 1785, Mozart wrote a set of string quartets thought to be inspired by Haydn's Opus 33 series. On completion he dedicated them to Haydn, a very unusual thing to do at a time when dedicatees were usually aristocrats. The extremely close 'brotherly' Mozart-Haydn connection may be an expression of Freemasonic sympathies as well: Mozart and Haydn were members of the same Masonic lodge. Mozart joined in 1784 in the middle of writing those string quartets subsequently dedicated to his Masonic brother Haydn. This lodge was a specifically Catholic rather than a deistic one.

In 1789, Haydn developed another friendship with Maria Anna von Genzinger (1750–93), the wife of Prince Nicolaus's personal physician in Vienna. Their relationship, documented in Haydn's letters, was evidently intense but platonic. The letters express Haydn's sense of loneliness and melancholy at his long isolation at Eszterháza. Genzinger's premature death in 1793 was a blow to Haydn, and his F minor variations for piano, Hob. XVII:6, which are unusual in Haydn's work for their tone of impassioned tragedy, may have been written as response to her death.

The London journeys

In 1790, Prince Nikolaus died and was succeeded by a thoroughly unmusical prince who dismissed the entire musical establishment and put Haydn on a pension. Thus freed of his obligations, Haydn was able to accept a lucrative offer from Johann Peter Salomon, a German impresario, to visit England and conduct new symphonies with a large orchestra.

The visit (1791-2), along with a repeat visit (1794-5), was a huge success. Audiences flocked to Haydn's concerts, and he quickly achieved wealth and fame: one review called him "incomparable." Musically, the visits to England generated some of Haydn's best-known work, including the Surprise, Military, Drumroll, and London symphonies, the Rider quartet, and the Gypsy Rondo piano trio.

The only misstep in the venture was an opera, L'anima del filosofo, which Haydn was contracted to compose, and paid a substantial sum of money for. Only one aria was sung at the time, and 11 numbers were published; the entire opera was not performed until 1950.

Final years in Vienna

Haydn actually considered becoming an English citizen and settling permanently, as composers such as Handel had before him, but decided on a different course. He returned to Vienna, had a large house built for himself, and turned to the composition of large religious works for chorus and orchestra. These include his two great oratorios The Creation and The Seasons and six masses for the Eszterházy family, which by this time was once again headed by a musically-inclined prince. Haydn also composed the last nine in his long series of string quartets, including the Emperor, Sunrise, and Fifths quartets. Despite his increasing age, Haydn looked to the future, exclaiming once in a letter, "how much remains to be done in this glorious art!"

In 1802, Haydn found that an illness from which he had been suffering for some time had increased greatly in severity to the point that he became physically unable to compose. This was doubtless very difficult for him because, as he acknowledged, the flow of fresh musical ideas waiting to be worked out as compositions did not cease. Haydn was well cared for by his servants, and he received many visitors and public honours during his last years, but they cannot have been very happy years for him. During his illness, Haydn often found solace by sitting at the piano and playing Gott erhalte Franz den Kaiser, which he had composed himself as a patriotic gesture in 1797. This melody later became used for the Austrian and German national anthems, and is the national anthem of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Haydn died in 1809 following an attack on Vienna by the French army under Napoleon. Among his last words was his attempt to calm and reassure his servants as cannon shots fell on the neighbourhood.

Character and appearance

Haydn was known among his contemporaries for his kindly, optimistic, and congenial personality. He had a robust sense of humour, evident in his love of practical jokes and often apparent in his music. He was particularly respected by the Eszterházy court musicians whom he supervised, as he maintained a cordial working atmosphere and effectively represented the musicians' interests with their employer; see Papa Haydn.

Haydn was a devout Catholic who often turned to his rosary when he had trouble composing, a practice that he usually found to be effective. When he finished a composition, he would write "Laus deo" ("praise be to God") or some similar expression at the end of the manuscript. His favourite hobbies were hunting and fishing.

Haydn was short in stature, perhaps as a result of having been underfed throughout most of his youth. Like many in his day, he was a survivor of smallpox and his face was pitted with the scars of this disease. Haydn was quite surprised when women flocked to him during his London visits as he did not consider himself to be handsome.

About a dozen portraits of Haydn exist, although they disagree sufficiently that, other than what is noted above, we would have little idea what Haydn looked like were it not also for the existence of a lifelike wax bust and Haydn's death mask. Both are in the Haydnhaus in Vienna, a museum dedicated to the composer. All but one of the portraits show Haydn wearing the grey powdered wig fashionable for men in the 18th century, and from the one exception we learn that Haydn was bald in adulthood.

Works

Haydn is often described as the "father" of the classical symphony and string quartet. In fact, the symphony was already a well-established form before Haydn began his compositional career, with distinguished examples by Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach among others, but Haydn's symphonies are the earliest to remain in "standard" repertoire. His parenthood of the string quartet, however, is beyond doubt: he essentially invented this medium singlehandedly. He also wrote many piano sonatas, piano trios, divertimentos and masses, which became the foundation for the Classical style in these compositional types. He also wrote other types of chamber music, as well as operas and concerti, although such compositions are now less known. Although other composers were prominent in the earlier Classical period, notably C.P.E. Bach in the field of the keyboard sonata (the harpsichord and clavichord were equally popular with the piano in this era) and J.C. Bach and Leopold Mozart in the symphony, Haydn was undoubtedly the strongest overall influence on musical style in this era.

The development of sonata form into a subtle and flexible mode of musical expression, which became the dominant force in Classical musical thought, owed most to Haydn and those who followed his ideas. His sense of formal inventiveness also led him to integrate the fugue into the classical style and to enrich the rondo form with more cohesive tonal logic, (see sonata rondo form). Haydn was also the principal exponent of the double variation form, that is variations on two alternating themes, which are often major and minor mode versions of each other.

More Genres

No Artists Found

More Artists

Load All

No Albums Found

More Albums

Load All

No Tracks Found

Genre not found

Artist not found

Album not found

Search results not found

Song not found

Symphony No. 98 in B-flat major Hob. I:98: IV. Finale. Presto

Franz Joseph Haydn Lyrics

No lyrics text found for this track.

The lyrics are frequently found in the comments by searching or by filtering for lyric videos

The lyrics are frequently found in the comments by searching or by filtering for lyric videos

@elaineblackhurst1509

You raise an interesting point which is worth considering.

By the time of Haydn’s two visits to England in 1791 - 92, and 1794 -95, the harpsichord was a very old-fashioned instrument indeed.

London fortepiano makers such as Broadwood, and Longman & Broderip were building new fortepianos which were some of the biggest, and most advanced in Europe (though they had a heavier action than Austrian models known to Mozart, and to Haydn hitherto).

A familiarity with these more powerful instruments is reflected in Haydn’s late keyboard works.

During his first stay in London, Salomon arranged for Haydn to use a room at Broadwood’s shop* for composing, and he obviously got to know the instruments very well.

* Haydn signed Broadwood’s guest book on 26 September 1791.

The little solo he wrote for himself at the end of the finale was intended for a fortepiano, not a harpsichord, though he did mark it ‘cembalo solo’ in the score.

@elaineblackhurst1509

@@christianwouters6764

Some interesting points.

Robbins Landon is clear that the news of Mozart’s death did reach London whilst Haydn was composing Symphony 98.

(Haydn mentions his friend’s death as early as January 1792 in a letter he sent back to Vienna).

I believe Mozart’s death to be coincidental, and not relevant to the spirit of the Adagio which is directly aimed at his English audience and an acknowledgement of them through a shared knowledge and understanding of God Save the King; it is nothing to do with Mozart whom Haydn found ‘…almost unknown in England’.

The slow, profound, hymn-like mood of the Adagio is also very un-Mozartian,* and if it were a tribute to Mozart, would he not perhaps have quoted Mozart specifically in the manner Mozart did in the piano concerto K414** when he heard of the death of JC Bach - something of which Haydn would have been well aware.

* Mozart wrote no symphonic slow movements - they are all Andante-type without exception (though there are slow introductions to Symphonies 36, 38, and 39).

** Mozart quotes directly and unambiguously from the Andante grazioso second movement from overture to JC Bach’s opera La calamita de’ cuori.

@elaineblackhurst1509

@@christianwouters6764

I’m not sure that it was via a letter that Haydn found out about the death of Mozart, though it could well have been so.

This is one of those occasions when a little wider historical context is important in piecing together a story.

London was full of foreign musicians, something which during the 1790’s was particularly evident following the events of the French Revolution of 1789 and subsequent French wars which led to a number of refugees arriving in England fleeing from France.

The turmoil and movement inevitably led to news being spread rapidly via word of mouth.

Haydn knew about the death of Mozart as early as January 1792; he wrote to Michael Puchberg (well known to both Mozart and Haydn) in a letter dated that month from London that begins:

‘For sometime I was beside myself about his [Mozart’s] death…’.

The letter can be found in Robbins Landon’s Collected Correspondence and London Notebooks of Joseph Haydn, and is quoted and referenced again in Robbins Landon’s biography -

Haydn: Chronicle and Works, Volume 3, Haydn in England 1791-1795, page 121.

Despite the pan-European turmoil that lasted on-and-off until 1815, Haydn seems to have had little trouble dealing with up to six different publishers in Great Britain, and neither cost nor time ever seemed to be a problem.

Occasional letters went missing, but that happened sometimes even on the relatively short journey from Eszterhaza to Vienna up to 1790.

In short, there is no doubt whatsoever that Haydn knew of the death of Mozart little more than a month after the event.

@elaineblackhurst1509

Not sure the first or second movements could be described as ‘genial’, nor really the contrasting second half of the symphony.

Right from the outset, the ominous B flat minor theme that foreshadows the B flat major of the following Allegro is quite eerie.

The first movement as a whole is rigorously worked-out and you need to concentrate hard to follow the sophisticated musical argument which includes some intense contrapuntal work.

All this - and much more - is anything but genial.

The second movement is sublime and profound; the central minor key section is turbulent and stormy - again, there is no geniality here at all.

Haydn 98 is a serious and weighty symphony that makes a real emotional statement, particularly in the first two movements; Haydn then relaxes the intensity and changes the mood in the final two movements in order to balance the content.

The finale in particular, is a masterclass of playful ingenuity.

You’re quite right though that with every Haydn symphony you come to know, one never ceases to be amazed.

(Subsequent note: it’s possible we may have a false-friend here - for example genial (English) and geniale or genialità (Italian)

@Mahlerweber

Very nice. I had an old recording which I no longer own. I was expecting a harpsichord toward the finale, but the piano substitute was really refreshing.

@elaineblackhurst1509

You raise an interesting point which is worth considering.

By the time of Haydn’s two visits to England in 1791 - 92, and 1794 -95, the harpsichord was a very old-fashioned instrument indeed.

London fortepiano makers such as Broadwood, and Longman & Broderip were building new fortepianos which were some of the biggest, and most advanced in Europe (though they had a heavier action than Austrian models known to Mozart, and to Haydn hitherto).

A familiarity with these more powerful instruments is reflected in Haydn’s late keyboard works.

During his first stay in London, Salomon arranged for Haydn to use a room at Broadwood’s shop* for composing, and he obviously got to know the instruments very well.

* Haydn signed Broadwood’s guest book on 26 September 1791.

The little solo he wrote for himself at the end of the finale was intended for a fortepiano, not a harpsichord, though he did mark it ‘cembalo solo’ in the score.

@gabrielkaz5250

27:38

@winterdesert1

OMG. This is incredible.

@maxfochtmann9576

Спасибо за запись. Превосходно.

@adamrowe8674

The similarities between this and the slow introduction of the first movement Beethoven's fourth symphony in the same key are striking

@elaineblackhurst1509

The point about the extraordinary b flat minor (sic) Adagio introduction is that it is a clear foreshadowing of the B flat major Allegro that follows.

Forget Beethoven: in many respects this symphony is a significant evolutionary event in its own right.

The opening minor/major theme is developed extensively - including contrapuntally - and towards the end, taken on a highly unlikely tonal journey.

The rest of the symphony is full of new ideas, inspiration, and overall, is a work of the highest originality and genius.

@BlueMeeple

More striking is the similarity between the beginning of 2nd movement and God Save the Queen. :D

@elaineblackhurst1509

@@BlueMeeple

You make a good point; it is the mood and spirit of the British national anthem that pervades this Adagio movement rather than the entirely speculative notion of it being some sort of tribute to the recently deceased Mozart, a mistaken viewpoint that has been aired rather too often in the comments on this symphony.

@karllieck9064

I noticed that right away. Lo!