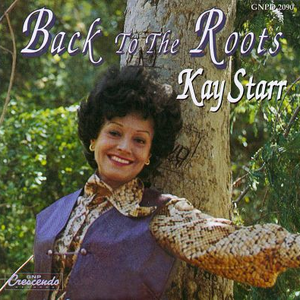

Kay Starr was successful in every field of music she tried, jazz, country and pop. But her roots were in jazz, Billie Holiday, considered by many the greatest jazz singer of all time, called Starr "the only white woman who could sing the blues."

She is best remembered for introducing two songs that became #1 hits in the 1950s, "Wheel of Fortune" and "The Rock And Roll Waltz".

Kay Starr was born on a reservation in Dougherty, Oklahoma. Her father, Harry, was a full-blooded Iroquois Indian; her mother, Annie, was of mixed Irish and American Indian heritage. When her father got a job installing water sprinkler systems, the family moved to Dallas, Texas.

While her father worked for the Automatic Sprinkler Company, her mother raised chickens, and Kay used to sing to the chickens in the coop. As a result of the fact that her aunt, Nora, was impressed by her singing, she began to sing at the age of seven on a Dallas radio station, WRR, first in a talent competition where she finished third one week and won every week thereafter, then with her own weekly fifteen minute show. She sang pop and "hillbilly" songs with a piano accompaniment. By the age of ten, she was making $3 a night, a lot of money in the Depression days.

As a result of her father's changing jobs, her family moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and she continued performing on the radio, singing "Western swing music," still mostly a mix of country and pop. It was while she was on the Memphis radio station WMPS that, as a result of misspellings in her fan mail, she and her parents decided to give her the name "Kay Starr". At the age of fifteen, she was chosen to sing with the Joe Venuti orchestra. Venuti had a contract to play in the Peabody Hotel in Memphis which called for his band to feature a girl singer, which he did not have; Venuti's road manager heard her on the radio, and suggested her to Venuti. Because she was still in junior high school, her parents insisted that Venuti take her home no later than midnight.

Although she had brief stints in 1939 with Bob Crosby and Glenn Miller (who hired her in July of that year when his regular singer, Marion Hutton, was sick), she spent most of her next few years with Venuti, until he dissolved his band in 1942. It was, however, with Miller that she cut her first record: "Baby Me"/"Love with a Capital You." It was not a great success, in part because the band played in a key more appropriate for Marion Hutton, which was less suited for Kay's vocal range.

Limehouse BLues

Kay Starr Lyrics

Jump to: Overall Meaning ↴ Line by Line Meaning ↴

Never go away

Sad, mad blues

For all the while they seem to say

Oh, Limehouse kid

Oh, oh, Limehouse kid

Goin' the way

Poor broken blossom

And nobody's child

Haunting and taunting

You're just kind of wild

Oh, Limehouse blues

I've the real Limehouse blues

Can't seem to shake off

Those real China blues

Rings on your fingers

And tears for your crown

That is the story

Of old Chinatown

Rings on your fingers

And tears for your crown

That is the story

Of old Chinatown

In this song, "Limehouse Blues," Kay Starr is describing a feeling that is unmistakably Chinese. She refers to "weird China blues" which never seem to go away, and they are "sad, mad blues." The lyrics suggest a lingering sadness that is part of a cultural identity, and the "Limehouse kid" who is "goin' the way/ that the rest of them did/ poor broken blossom/ and nobody's child" is emblematic of this identity.

The use of the word "weird" suggests an outsider's perspective on Chinese culture, since it is unlikely that anyone within that culture would refer to their own blues as "weird." The repetition of the word "blues" suggests a certain melancholy that is associated with this culture, as if it is always there in the background, even in moments of happiness.

The image of "rings on your fingers/ and tears for your crown" adds to the sense of sadness and loss associated with the Limehouse blues. The final lines of the song, "that is the story/ of old Chinatown" suggest that this is not a personal sadness, but one that is part of a larger cultural identity.

Line by Line Meaning

And those weird China blues

The unexplainable melancholy felt amongst the Chinese locals

Never go away

This sentiment is ever-present, never faltering

Sad, mad blues

Describing the sorrowful, disturbed emotions felt due to the experiences in Chinatown

For all the while they seem to say

Continuously and persistently expressing these emotions

Oh, Limehouse kid

Referring to someone who dwells in Chinatown

Oh, oh, Limehouse kid

Repeating the previous line for emphasis, highlighting the significance of the location

Goin' the way

Heading towards the same negative outcome

That the rest of them did

Following in the footsteps of those before them

Poor broken blossom

A reference to a female, 'broken' by the harsh experiences in Chinatown

And nobody's child

An orphan, facing the hardships of life alone

Haunting and taunting

The lingering presence of these troubling emotions, tormenting the individual

You're just kind of wild

Reacting to the circumstances in a somewhat irrational or uncontrolled manner

Oh, Limehouse blues

Referencing the melancholy and sorrow in Chinatown

I've the real Limehouse blues

Personally experiencing this location and its negative effects

Can't seem to shake off

Unable to rid oneself of these emotions

Those real China blues

The genuine emotional struggle experienced by the inhabitants of Chinatown

Rings on your fingers

Wearing expensive jewelry as a sign of wealth or status

And tears for your crown

Crying despite this façade of prosperity

That is the story

This is a common narrative amongst the locals

Of old Chinatown

Referring to the significant location that has had a negative impact on many inhabitants throughout time

Lyrics © Warner Chappell Music, Inc.

Written by: Douglas Furber, Philip Braham

Lyrics Licensed & Provided by LyricFind